Around this last year, Kenny Easley was recovering from triple bypass surgery when he received a phone call that helped lift his spirits and renew his faith. Nearly 30 years removed from his final season in the NFL, and a few weeks removed from a significant operation, Easley found out he was a finalist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame, an honor he long ago had figured wasn't in the cards for him.

"I was sort of down in the dumps," Easley said. "I couldn't imagine that this heart that had done everything I had asked of it as an athlete could have failed me. That was a difficult period for me. But two weeks after I got out of the hospital, I get a phone call telling me that I'm a finalist in the senior division for the Pro Football Hall of Fame. That just completely changed me spiritually."

That good news, which was followed in February by Easley being voted into the Hall of Fame, helped validate something he had heard from Tyrone Armstrong, the pastor at the church he attends in Chesapeake, Virginia.

"He gave me a bible verse, Philippians 4:6, 'Be anxious for nothing.' And that always resonated in my soul, that if I was patient and it was God's will, then it would happen," Easley said.

Easley's patience paid off, and this weekend in Canton, Ohio, he will become the fourth Seahawk, along with Steve Largent, Walter Jones and Cortez Kennedy, to go into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

"It just changed everything spiritually for me," Easley said of receiving that phone call last summer. "I got up, started walking, started doing all kinds of things to get my health back… That was significant, that was really significant in my life."

As significant as enshrinement into the Pro Football Hall of Fame is to Easley, he can't yet put the meaning of that honor into words. Easley has such reverence for this honor that, until he actually goes through the ceremony this weekend and puts on that gold jacket, he won't try to describe what it means to him.

"You don't know how to feel," Easley said last week. "I've done a number of interviews, and the reporters always ask, 'How does it feel?' My comment has been, the Hall of Fame is something that is difficult to get your arms around. When you think of the magnitude of this thing, that there are only 310 members, and basically 175 still living, and you think of the thousands of football players since the league was founded, it's hard to get your arms around the fact that you are part of this exclusive group. So for me, when I make my definitive comment on what it feels like to be a Hall of Famer, I want it to be a significant statement for a significant event. So I want time to get my arms fully around it, to go through the ceremony, the induction, all the things we'll go through, then sit down and try to come up with a statement that'd indicative of the event."

Yet even if Easley can't yet put what this means to him into words, People close to him have seen a change over the past year as he found out he was headed towards football immortality. Gone were the bad moods and low energy, replaced by improved health and a better outlook on life.

"He has absolutely changed," said Kendrick Easley, Kenny's son. "The energy has picked up, he's a lot more positive. Since this Hall of Fame stuff started, his perspective has really changed and he's in a really good place now."

"Kenny was one hell of a player… This was way overdue."

Kendrick Easley was talking about his dad on the driving range at the White Horse Golf Club in Kingston where his father was hosting his annual golf tournament to raise money for the Greater Trinity Academy. With Easley's Hall of Fame enshrinement approaching, the driving range became a trip down memory lane for other former players who had played with or against Easley, all of whom were thrilled to see Easley finally earn this honor.

"Kenny was one hell of a player, no doubt about it," said former University of Washington cornerback Mark Lee, who recently went into the Green Bay Packers Hall of Fame. "He had a tremendous career in the NFL. Kenny is one of those guys who was a heck of a smart player. You could see him out there lining guys up on the field… I think he should have been in a long time ago, but it's better late than never. He definitely deserves it.

"Defensive backs always look at the other great defensive backs to see if we can pick anything, and that's how I always looked at Kenny. He was a smart player; he knew the offense before they came out on the field. And he's a big-time hitter, he'll put it on you. This was way overdue, I'm really happy for him."

Before his friends headed off to the first tee—Easley gave up golf years ago, but still enjoys himself as the host of this event—Easley and former Seahawks cornerback Terry Taylor laughed about the times when they would change the defensive play-call on the field, much to the chagrin of defensive coordinator Tom Catlin. But Catlin could only get so upset, Taylor said, because his and Easley's audibles almost always worked.

"Man, let me tell you this, Kenny Easley is like a big brother to me," said Taylor, who was a first-round pick in 1984. "Kenny Easley, Dave Brown, John Harris and Keith Simpson, those guys took me in as a rookie at taught me how to play the game. I used to go to Kenny's house and watch film—he taught me how to watch film. I owe a lot to him, I'm going to tell you that right now. I wouldn't have picked up the game as quickly as I did without him."

Taylor is also convinced that he enjoyed a long career in part because of some sound advice given to him by Easley during his rookie season.

"My rookie year, I come up and made a tackle, a really hard tackle, and Kenny came up to me and said, 'Hey, Taylor, listen, you can't be tackling people like me. We need you to be able to play the whole game. You tackle somebody like that, you're going to hurt yourself,'" Taylor said. "That's the best advice that man ever gave me. He said, 'You're too little to be out there smashing people like me. We love seeing you do it, but you're going to kill yourself.'"

Yet it wasn't Easley's ability to make his teammates better that got him into the Hall of Fame; it was his dominance during a relatively short career, which was cut short by a kidney ailment. In seven seasons, Easley earned Pro-Bowl honors five times and was named Associated Press first-team All-Pro three times. A member of the 1980s all-decade team, Easley was also the NFL's Defensive Player of the Year in 1984 when he had a league-high 10 interception while helping the Seahawks to a 12-win season.

"I've always said Kenny was a Hall of Famer," Taylor said. "Even if he would have never made it, I knew who I played with. He was the best player on our team, I'll tell you that right now. He was well deserving of this, it should have happened 25 years ago. I'm so happy for him."

Hall of Fame safety Ronnie Lott, who was a rival of Easley in college when they played at USC and UCLA, respectively, has spent years advocating for Easley to get into the Hall of Fame.

"I can tell you many moments of watching Kenny Easley, because that's what I used to spend my time doing, watching Kenny Easley," Lott said in a video congratulating Easley on his enshrinement. "The reason why? There was no one that got me excited about playing the game of football than when I watched him… There's no one more deserving."

Another player who marveled at Easley from afar before becoming his friend is Nesby Glasgow, who played at Washington before beginning his NFL career with the Colts. Glasgow eventually played for the Seahawks, but not until after Easley had retired.

"It's one of those things that's definitely long overdue," Glasgow said. "When you talk about great players in the league, when you're talking about a guy who really set a standard for the position, he'd be in anybody's conversation. We looked at him in awe as defensive players, so I know the offensive guys were intimidated by him.

"Some guys are really tough and some guys aren't, and for Kenny, every time he stepped on the football field, he gave you everything he had, and because of that, he had a lot of guys that followed him. When you look at his size and his range and athleticism, he had all the ingredients you look for to play that position. It's long overdue. He earned it the hard way by imposing his will on a lot of other great athletes."

"I was wallowing in my own anger."

As a child, Kendrick Easley knew his father had been a professional football player, but he didn't know that Kenny Easley was, well, Kenny Easley. That's because for the first 15 years of Kendrick's life, and the first 15 of Kenny's retirement, the elder Easley had no relationship with his former team or even the game of football. Easley felt wronged by the Seahawks for how his career ended, there was a lawsuit involving his kidney disease that was eventually settled in the 1990s, and for 15 years, Easley was, as he put it, "wallowing in my own anger."

Finally, in 2002, Easley reconciled with the Seahawks and went into the Seahawks Ring of Honor, and it was at that point that Easley's three children began to understand just how big of a deal their father was.

"I was at a loss for word," Kendrick said. "I was in shock to see the impact he left on the Seahawks and in the NFL. It definitely changed my perspective on what he did in the NFL, everything he accomplished. I had no idea. When I was living in Seattle, I knew he was a football player, but I didn't know how good he was until we moved away and I did some research. I also didn't know his relationship with the Seahawks was strained at that point. I'm happy to see that get repaired and see where he's at now.

"I'm very proud of him, very happy for him, because I know his journey, what he's been through. It was great for him, great for his spirit and his morale."

For Easley, reconnecting with the Seahawks happened for a number of reasons. For starters, he wanted his children to know more about who he was as a player, and his wife also pushed him, asking, 'How long can you hold a grudge? They've got a different owner, different doctors and trainers. All these people you believed injured you, they're gone.'"

The reunion with the Seahawks finally took place in 2002 in large part because Gary Wright, who at the time was the team's vice president of communications, reached out to see if Easley would come to Seattle to accept a spot in the Ring of Honor.

"It was simple, we couldn't put anyone else in the ring of honor before Kenny Easley," Wright said. "There were a lot of other great players, but it wouldn't have any credibility if he wasn't in first."

Easley accepted that invitation, his first step towards reconnecting with football, and now, 15 years after going into the Ring of Honor, he's set to earn the game's highest individual honor.

"It was good that the reconciliation happened," Easley said. "To be honest, I never gave it much thought, because I was wallowing in my own anger. I thought I was done unfairly, it didn't have to happen what happened to me, and it took me a while to get over that. For 15 years, I didn't watch a football game. I never saw Cortez Kennedy play a single game, because from 1987 to 2002, the night that I went into the Ring of Honor, I had not seen an NFL football game in that entire time. In fact, any kind of football, because I had to divorce myself from it completely."

But then Wright called, and Easley's wife, Gail, spoke up, and slowly old wounds began to heal.

"Just like that, I'm one of 310 Hall of Famers in the history of the NFL," Easley said. "Again, I can't say what it means yet. It has been a long time coming, it has been a long road, but it has been a road that for a long time I honestly never thought about, because I didn't think this day would come."

Take a look back at some of the best moments from the career of former Seahawks safety Kenny Easley, who was announced as part of the Pro Football Hall of Fame Class of 2017 on Saturday, February 4, 2017 in Houston, Texas the night before Super Bowl LI.

Seattle Seahawks Kenny Easley (45) is upended by an unidentified Los Angeles Raiders player during the first quarter of the AFC wild card game at the Kingdome in Seattle, Wash., Dec. 22, 1984. (AP Photo/Eric Risberg)

Los Angeles Raiders veteran running back Frank Hawkins (27) pushes his way across the goal line for his second touchdown of the day despite the defensive efforts of Seattle Seahawks Kenny Easley during first half action at the Coliseum on Sunday, Jan. 8, 1984 in Los Angeles. (AP Photo)

Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley (45) takes down Los Angeles Raiders tight end Todd Christensen (45) in a 30-14 loss to the Los Angeles Raiders in an AFC Championship game on January 8, 1984 at Los Angeles, California. 1983 AFC Championship Game - Seattle Seahawks vs Los Angeles Raiders - January 8, 1984 (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

Seattle Seahawks Kenny Easley came up with two interceptiions, looks for someone to lateral the ball to in a 35-13 win over the Los Angeles Raiders on October 25, 1987 at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum in Los Angeles, California. Seattle Seahawks vs Los Angeles Raiders - October 25, 1987 (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

Seattle Seahawk safety Kenny Easley during a 14-10 loss to the Los Angeles Raiders on October 12, 1986 at Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum in Los Angeles, California. Seattle Seahawks vs Los Angeles Raiders - October 12, 1986 (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

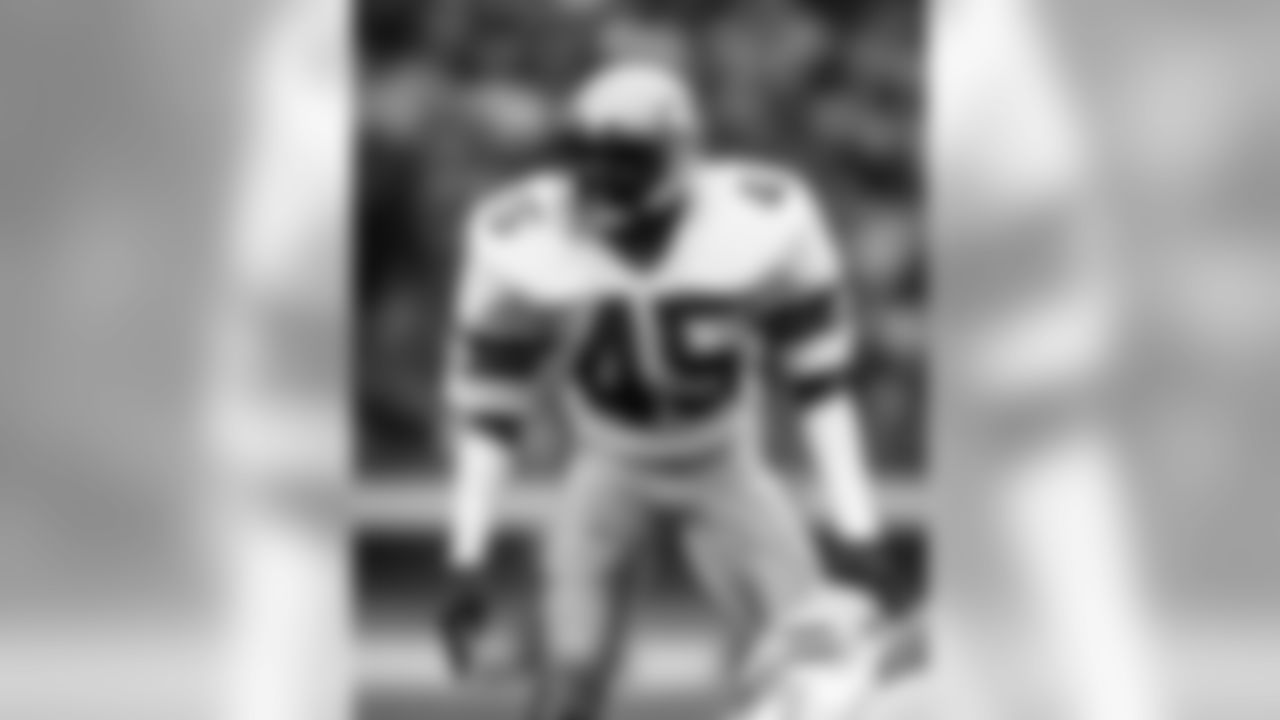

Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley (45) sets for play Dec. 29, 1984 in an AFC divisional playoff game in Miami. (Al Messerschmidt via AP)

Los Angeles Rams running back Eric Dickerson (28) tries to break a tackle by Seattle Seahawks strong safety Kenny Easley (45) during the NFL Pro Bowl football game between the AFC and the NFC in Honolulu, Hawaii on January 29, 1984. The NFC won the game 45-3. (AP Photo/Paul Spinelli)

Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley (45) sets for play in 1987. (Al Messerschmidt via AP)

Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley (45) celebrates a turnover in 1983 in Miami. (Al Messerschmidt via AP)

Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley (45) sets for play in 1987. (Al Messerschmidt via AP)

Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley (45) takes the field for play in 1987. (Al Messerschmidt via AP)

Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley (45) sets for play in 1987. (Al Messerschmidt via AP)

Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley (45) sets for play in 1987. (Al Messerschmidt via AP)

Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley (45) sets for play in 1987. (Al Messerschmidt via AP)

LOS ANGELES - OCTOBER 7: Safety Kenny Easley #45 of the Seattle Seahawks stops running back Derrick Jensen #31 of the Los Angeles Raiders at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum on October 7, 1984 in Los Angeles, California. The Raiders defeated the Seahawks 28-14. (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

Houston Oilers safety Keith Bostic shakes the hand of Seattle Seahawks safety Kenny Easley, both playing for the AFC, during the NFL Pro Bowl, a 15-6 AFC victory on February 7, 1988, at Aloha Stadium in Honolulu, Hawaii. (AP Photo/NFL Photos)

Head coach Pete Carroll chats with Seahawks legend and Ring of Honor member Kenny Easley before the game. Easley raised the 12 Flag before the game.